|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

It’s time to look at how we invite service participants into career conversations from a trauma-sensitive, systems-based approach. Right now, most career conversations, particularly at intake, are about what’s wrong with the service participant (often referred to as clients)1 and not so much about what’s happening for them. This intake practice starts the service participant off in a negative, diminished light and sets the career conversation up to be about ‘fixing problems’. This is a very barrier-centric way of beginning what could be a much more trauma-sensitive, systems-based conversation.

Current landscape

Intake forms (often including the language of ‘barriers’ or ‘multi-barriered client’) include a bevy of check boxes and personal information requirements to meet these various system members’ needs.

All of this happens before the service participant’s career conversation even begins. In this context, ‘barriers’ are used to determine whether the “right” interventions are being applied to meet the expectations of those further up the funding chain – a dynamic shaped by power imbalances. This way of framing intake invites us to pause and ask whose needs are being centred – and whose stories may be pushed to the margins.

This article is part of a themed CareerWise series highlighting topics gaining momentum at Cannexus26. For more timely insights from across the career and workforce development field, sign up for CareerWise Weekly.

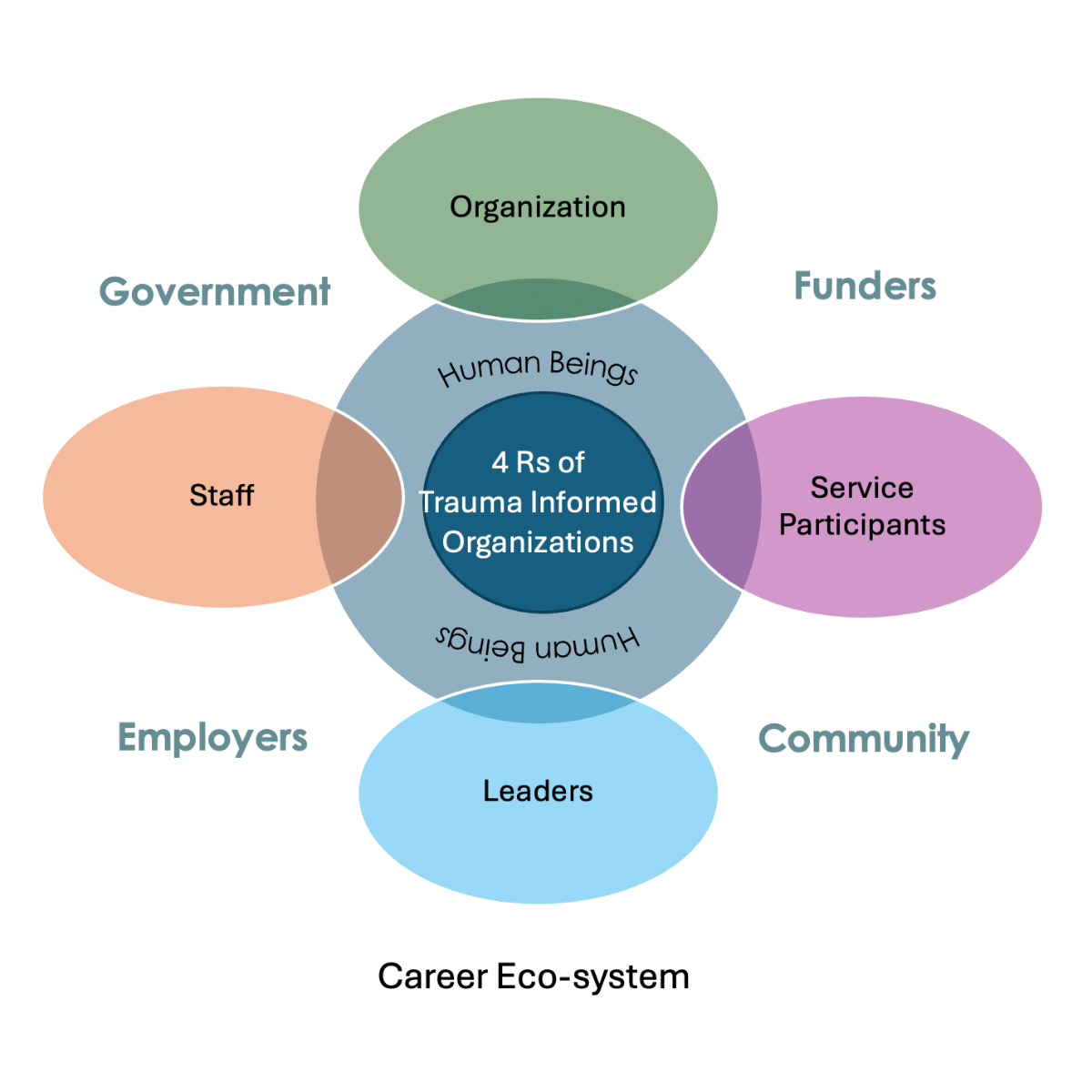

Below is a diagram that shows how each of these different parts of the career eco-system interact with each other from intake through to the career conversation and beyond. Funders, government, communities and employers sit at the outer edges of the career conversation. Closer in organizations, leaders, and staff and service participants form the central part of the interaction, which in the eco-system proposed here is centred on a trauma-sensitive approach.

Shifting perspective

The language we use at intake does more than describe reality – it shapes how responsibility, power and possibility are distributed across the career ecosystem. Barriers language centres those along the outer edges of the system – funders and governments – over the service participant. This approach focuses on what’s wrong with the individual, rather than exploring what is not working in the career eco-system.

From a trauma-sensitive, systems-based approach, the solution lies in the whole system – not the individual. Solutions that impact the service participant need to be system-wide. For example, in a rural Indigenous community outside of Vancouver, a major system-wide ‘barrier’ to service participant success was transportation. The career development professionals in the area, along with their organizational leadership, lobbied government to add a bus to their community to alleviate this systemic barrier with great success.

This example show how when we deepen our relationships with everyone in the system, we can change the system. This means inviting community members and employers into the career conversation. When barriers are systemic, the options for support lie not in what an individual service participant can do, rather, the possibilities lie in what capacity is available in their community. An individual experiencing ‘barriers’ to transportation for daily living and work is likely not going to be able to buy a car or create a bus route themselves but a community collaboration to connect underserved individuals in the community is much more feasible. When we orient towards creating impact networks – clusters of services, individuals and resources in the community – we can build capacity and create a more resilient labour market for all. We focus on community resilience, not on individualism.

Going forward

It’s time we start looking at the initial intake with service participants from a trauma-sensitive systems-based approach. When we ask about barriers, we are asking about what the individual is lacking. This approach centres the funder in the conversation and ignores the systems-based resources that may come to bear in the conversation.

What if we start asking what has happened to you? Or we start with what is happening for you? What brings you into this conversation today?

We shift the centring of the voice from the funder/government/organization to the service participant. We begin relationally, with care, through conversations, with pacing and spacing that works for the service participant. Ask yourself why we do intake the way that we do. Do we need to ask all of the questions up front in a contained time frame? Who does that approach attend to? This is not to say that we don’t need much of the information that is explored through the intake form. Instead, we are advocating a reorientation of intake that focuses on relationship building, that is rooted in conversation, in seeing the human being first, not forms.

With how we begin, what language we use and what orientations or perspectives we take, we can purposefully create belonging, trust and possibility at intake. If we flip the conversation to the service participant’s story we centre the relationship over the intake assessment and open up to engaging in trauma-sensitive, systems-based career conversations.

- The writers use the term service participant instead of client to denote the active way in which the individuals whom we serve are a part of the whole process and are not clinical recipients of our solutions.