Aging populations and workforce skills gaps are global challenges, not unique to Canada (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2018; United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, 2017; Statistics Canada, 2017, 2018). Long before the COVID-19 pandemic, as we noted in our article in the Canadian Journal for Career Development (Luke & Neault, 2020), the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD, 2015) and the International Labour Organisation (ILO, 2015) expressed concerns about how to engage older workers, including those in retirement, to enhance workforce productivity by re-injecting their skills.

The world has changed significantly in the early months of 2020 and older workers are now in a population considered most vulnerable to the ravages of the novel COVID-19 virus. However, many older workers may need to return to work to supplement lost family income or replenish pandemic-related losses in savings and investments. Now, more than ever, it’s important to consider how older workers can stay engaged, contributing their skills in a meaningful way while staying safe – especially in a transitional time of high unemployment as economies all over the world try to restart.

Motivation to work: Purpose and meaning

To begin, it is important to first focus on the individual. What are the needs of a mature-age worker? What does a retiree feel concerned about when deciding to re-engage with the workforce – and how might this be affected in the midst of a pandemic? What do they most hope to accomplish through a career transition? How does a mature age worker need to adapt to the changing world of work?

Throughout the research of Luke, McIlveen, and Perera (2016), retirement-age participants illustrated via their interview responses that they had an overall desire to know that their work and life experiences were of value and worth to the workplace. Dr. David Blustein (2011) emphasized that individuals of all ages seek meaning from their various life and career roles. They want to spend time in activities where both their personal values and perception of mattering contribute to purpose and meaning in their lives.

Career adaptability in transitions

Remaining adaptable and flexible in the face of challenges they may encounter during a search for meaningful work is key to all jobseekers, mature-age workers included. Measures of career adaptability incorporate four psychological dimensions: a sense of autonomy over work tasks (control), a future-focused orientation to working (concern), feeling positive about successfully contributing to a workplace (confidence), and a focus on lifelong learning (curiosity) (Savickas, 2012).

Technical capabilities are also important, of course, making constant up-skilling essential for most workers. This is especially true in the restarting of the global economy in the midst of a pandemic – we are all learning new ways to work and interact. The mature-age workers who are happy to retrain and upskill are most likely to be in demand and highly active until they choose to retire. Their flexibility, product knowledge, life experiences and willingness to accept short-term contracts or part-time work may make them especially valuable additions to workforces in transition.

Career engagement

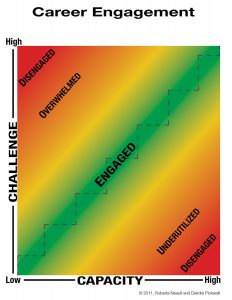

The Career Engagement model (Neault & Pickerell, 2019) offers another lens for attracting and retaining mature-age workers. Engagement is found at the intersection of challenge and capacity – too much challenge can be overwhelming but too little leaves one feeling underutilized. Individuals are not all ready to retire at the same age – finding the right balance of challenge and resources can help them to continue to make valuable contributions to their workplace and community long after they may otherwise have retired.

The challenge and implications for practice and policy

Our recent Canadian Journal for Career Development article (Luke & Neault, 2020) provides an international (trans-Pacific) perspective on the value of older workers, how to meet their workplace needs and expectations, and what it will take for them to achieve and sustain an optimal level of career adaptability and career engagement. The article provides contextualized career strategies, including vignettes based on interviews with post-retirement-age workers (Luke, Mcllveen, & Perera, 2016), that will inform both local and global workforce policy as well as stimulate professional practice conversations. The article demonstrates how the career engagement model can provide a practical conceptual framework for influencing policy and supporting career decision-making and lifelong career management for older workers that includes those in retirement who plan to re-engage with the workforce.

In the context of a pandemic, however, employers, policy-makers, and family members may be reluctant to risk the health and safety of mature-age workers who fall within an age group that has been identified as particularly vulnerable to the COVID-19 virus. Therefore, facilitating career engagement may require modifications and accommodations such as careful sanitization, working from home and/or physical distancing. However, mature-age workers who are needed at work and want to contribute must not be excluded from opportunities – they have much to offer.

References

Blustein, D. L. (2011). A relational theory of working. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 79(1), 1-17.

International Labor Organization (ILO). (2015). World employment and social outlook: Trends 2015. International Labor Organization, Geneva.

Luke, J., McIlveen, P., & Perera, H.N. (2016). A thematic analysis of career adaptability in retirees who return to work. Frontiers in Psychology. 7:193.

Luke, J., & Neault, R. A. (2020). Advancing older workers: Motivations, adaptabilities, and ongoing career engagement. Canadian Journal of Career Development, 19(1), 48-55.

Neault, R., & Pickerell, D. (2019). Career engagement: A conceptual model for aligning challenge and capacity. In N. Arthur, R. Neault, & M. McMahon (Eds.), Career theories and models at work: Ideas for practice (pp. 271-282). Toronto, ON: CERIC

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2015). Pensions at a glance 2015: OECD and G20 indicators. Paris, OECD

Savickas, M. L. (2012). Career construction theory and practice. In R.W. Lent & S.D.Brown (Eds.), Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work (2nd ed.).Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. (pp. 42-70). Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.