|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Addressing workplace trauma – whether that be trauma that occurs in the workplace or the effects of trauma that come into the workplace through the personal histories of staff and clients alike – requires a systems perspective.

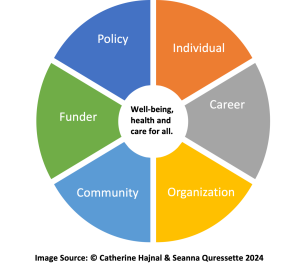

What does it mean for us to take a systems perspective in our work as career professionals? First and foremost is for us to recognize that we are indeed part of a system. When we look at what affects clients’ well-being, we often start with the individual. We engage in trauma-informed practices to foster well-being for our clients as we embrace values such as safety, mattering, belonging, connection, transparency and choice. As we engage with our clients, we recognize that there are many factors that are systemic and structural that influence what is happening for them. We recognize the interconnectedness of the individual with family, community, organizations, funders and policy-makers.

As career professionals, we are not separate from this interconnectedness. We, too, are individuals – personally and professionally a part of systems.

What if we are all responsible for and impacted by systems? How might we bridge individual interactions with our clients, their well-being, our well-being and the systems we are all a part of?

Trauma isn’t ‘out there,’ it’s within us

Trauma is defined as “an invisible unhealed wound caused by an overwhelming event, series of events or enduring conditions that remains active in our bodies, our psyches and our ways of relating to others.” This brings awareness to trauma being the effects or impacts of events, rather than the events themselves. This is why two individuals can experience the same traumatic event very differently. Notice, too, that trauma can be connected to chronic conditions – for example, discrimination, food scarcity, emotional neglect, substandard wages, housing scarcity or a years-long pandemic.

To offer some context, approximately 70% of the world’s population has been exposed to a traumatic life event. Six out of 10 have experienced one or more adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), which represent a threat to well-being. We also know that these numbers are higher for those who experience marginalization. While not everyone exposed to a traumatic event is living with a post-traumatic stress diagnosis, our understanding of trauma impacts is broadening, as evidenced by the ACEs pyramid.

This article is part of a CareerWise series on “Trauma and Career Development.” Read more:

- Supporting staff retention with trauma-informed supervision

- Resources exploring trauma and career motivation

What this means for our work

If trauma lives in our nervous system, then we need to recognize that it is not something that we or our clients can “leave at the door”; it is with us wherever we go and will be reflected in how we connect with each other and in how we make decisions. We may not consciously be aware we have an unhealed wound.

When we appreciate that career conversations are happening in the broader context of our own lives and those of our clients, it invites different conversations. This does not mean that we take it all on; it is not our job as career practitioners to heal trauma effects. Rather, we look at how our work intersects with the social determinants of health and well-being.

Take, for example, the scenario of needs for housing and/or mental health support that arise in the context of a career conversation. In many communities – whether urban, rural or remote, Indigenous or non-Indigenous – networks for referrals may be limited or non-existent. There may be no one to refer to, wait times for access to a referral source may inhibit any immediate care, and/or access to a referral source may require transportation, childcare, housing or funding – all of which may also be unavailable or cost prohibitive. All of this assumes we even have the time and capacity to develop referral networks in the first place. Working in trauma-informed ways challenges the whole system.

This invites us to acknowledge that trauma is in our systems as well. How policy is established, what policy is established, how our organizations are set up and managed, how our profession is set up and evolves. All of this is rooted in who we are as individuals and in what has come before us – intergenerationally and systemically. Consider all of the biases – racism, misogyny, ableism, to name but a few – that have influenced policy, the design of organizations, the design of work, the design of cities and communities.

What we can do

In these moments of awareness of the prevalence of trauma in our systems, we sometimes experience a sense of overwhelm, of despair, of anger. We mourn and we long for things to be different. And then we ask what we can do in this moment with the platforms and privilege we have, with the daily interactions we have with our clients, with our referral networks and in how we interact with our colleagues.

We offer the following guideposts for our actions:

- Acknowledge that trauma is not “out there.” It is in us – all of us. We have individual work we need to do to heal ourselves. You are doing this, in part, by being curious in this way.

- We start to advocate within our communities. This makes each of us responsible for our collective well-being. We step into difficult and awkward conversations in our communities by asking poignant questions. We question funding models and leadership – are their approaches trauma informed? Are we collectively recognizing the presence of trauma? We talk about trauma and the social determinants of mental health and well-being, building trauma-informed referral networks.

- We do this work in trauma-informed ways, recognizing right-sized actions: small enough to be achievable, large enough to be meaningful, using trauma-informed concepts like pacing and spacing to support nervous system regulation. This means we don’t hold everyone to contribute to care in the same way; rather, it will be based on the capacities that each of us has as an individual – personally and professionally – and what systems we engage with. It means we cannot move people through our programs at the same pace.

- We acknowledge that some people need to work on their mental health concerns before working on employment-related tasks. These are ways of looking at pacing, spacing and right-sized actions.

From the parts to the whole

When we apply this systems perspective to working in trauma-informed ways within career conversations, we bring tools to work with all parts of the system – not just holding the individual responsible for managing their own trauma and the trauma in the system.

During our webinar, we will explore the following concepts: systems-oriented thinking; the well-being continuum, the way to have conversations that support individual progress within systems and how to have difficult and awkward conversations.

More from Catherine Hajnal and Seanna Quressette:

- The importance of uncomfortable conversations: Suicide ideation

- Working toward trauma-informed funders in career development

- What it means to ‘help’: Asking ourselves the uncomfortable questions as advocates

- Working toward trauma-informed career development organizations

- What it means to consider trauma within career development