“Well, what is your job anyways?” (or, as interpreted by my inner voice, “What help/use are you?”). This feedback is never a great way to start a career conversation. It was especially difficult since it happened during my first year as a career advisor, and because the man before me – about 30 years my senior – seemed to expect an oral defence on the subject. What made the situation so surprising at the time was the speed with which our conversation ran off the rails. Looking back, however, I see that our discussion was sabotaged by a misalignment of expectations.

In this scenario, the client – I’ll call him Aaron – had presented me with what he deemed all the relevant “biodata” of his case in the form of documents, resumes and a short narrative. In return, he expected that I would analyze the data, factor local industry trends into a formula and spit out the perfect solution for his mid-to-late-life career needs. My attempts to add nuance to the conversation were perceived as a refusal to help, and he was quick to point out what, to him, was the obvious function of a career advisor – namely, to tell him which career he should pursue.

Previously, in CERIC’s Careering magazine and on the GSEP (Graduate Student Engagement Program) Corner, I wrote about the importance of taking a contextual approach to working with clients and other context-dependent expectations that arise in career advising. In the example above, part of the disconnect with Aaron was due to our differing contexts. Since Aaron was a newcomer to Canada, it was critically important for me to understand that labour/employment is not organized uniformly around the globe. At that point in time, my own experience had not prepared me to understand that culture, globalization, previous education, socio-economics and individual experience are “teachers” that inform clients’ beliefs. Aaron’s personal context led him to expect a certain kind of service and misunderstand what I could provide him as a career advisor. Likewise, my personal context had not prepared me to recognize such misunderstandings.

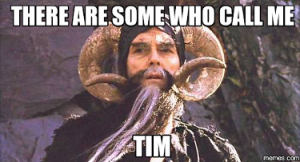

Client: What manner of man are you that can summon up personally relevant career information without books or the internet?

Me: I am a career advisor – but that’s not entirely accurate …

Client: By what name are you known? Me: There are some who call me … Taylor?

(Caption: Watch the clip here.)

In The Holy Grail, part of the humour of the “Tim the Enchanter” sketch is the dissonance between a commonplace name like “Tim” and the supernatural power this particular Tim wields. I felt more like a regular “Tim,” but from my perspective, Aaron was looking for “the Enchanter” – someone with magical career match-making abilities.

However unreasonable I thought that expectation was at the time, it is worth remembering that this is not the only sort of misaligned expectation career practitioners face: some expectations I see are about the job market, where clients mythologize “what’s hot” as a secret knowledge of careers that are impervious to market crises or governmental defunding. Others expect a guarantor: someone to hold accountable for their next decision or for a choice they made in the past. Some expect the perfect balance of information to make their career decision easy.

Unfortunately, career decisions are rarely easy. I know that I can’t meet these expectations the way these client archetypes wish me to and, ethically, I don’t want to lead them on. Therefore, career practitioners often face the challenge of determining how to offset client expectations without undermining their expertise or legitimacy.

Connecting and setting the objective

Encouraging a client to engage in the difficult task of reflecting on their complex, contradictory and changing world is no easy ask – especially when they expect an “expert” to make the decision for them – but that is the goal. In his book, Education at the Crossroads, Jacques Maritain notes it is not just an educator’s job to answer the questions learners know to ask, but also the “questions and difficulties with which the mind of the… [learner] may be entangled without being able to give expression to them” (p. 43). Likewise, in the career office, practitioners must bypass expectation barriers to guide clients through the humanizing process of identifying underlying career concerns and developing the agency to address them.

“Some expectations I see are about the job market, where clients mythologize ‘what’s hot’ as a secret knowledge of careers that are impervious to market crises or governmental defunding.”

At Northern Alberta Institute of Technology’s Transition Services, we have connected our career advising approach to the institution’s best practices in instructor training. Each career advising conversation begins in the same manner as creating a lesson plan, by “Connecting” and co-constructing a realistic objective with the client for the session. “Connecting” humanizes classrooms by centring education on learners, building rapport and helping educators understand where their learners are situated. In career advising, “Connecting” involves starting a conversation with simple, open-ended questions to better understand the client and their narrative, rather than getting straight to business. By connecting with the client, we build rapport, which helps when negotiating space around the client’s expectations. For example, one of my favourite humour-based, expectation-dispelling “spells” is, “I’ve known you for about five minutes now, so I’m probably a bad person to decide what will happen in the next 10 years of your life.”

What happens after you dispel a client’s misaligned expectations is equally as important as dispelling them in the first place. It is only natural for a client to then wonder, “Why am I here?” Before getting started on career-exploration activities, the practitioner and client need to agree on new expectations, including defining roles, sharing responsibilities, setting boundaries, establishing goals for the session and the action plan, and reassuring the client by providing an appropriate way to follow up.

Connecting and objective-setting are the processes of understanding the contextual realities of clients, actively addressing misaligned expectations and co-constructing a new direction for career conversations. Clients aren’t always ready to go down this road. That is all right as long as career advisors identify the discrepancy in expectations and understand their practice; it is okay to acknowledge when a working relationship is a mismatch. However, when connecting aligns expectations, career practice starts to feel like magic.

King Arthur: You know much that is hidden, oh Tim!

Tim the Enchanter: Quite.