|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Do you ever wonder why you are drawn to a helping profession? As career professionals, we constantly help people through life transitions in wide-ranging ways. Along with our knowledge, skills and abilities, we bring to this work our personal perspectives and frameworks on what it means to “help” and who exactly needs helping.

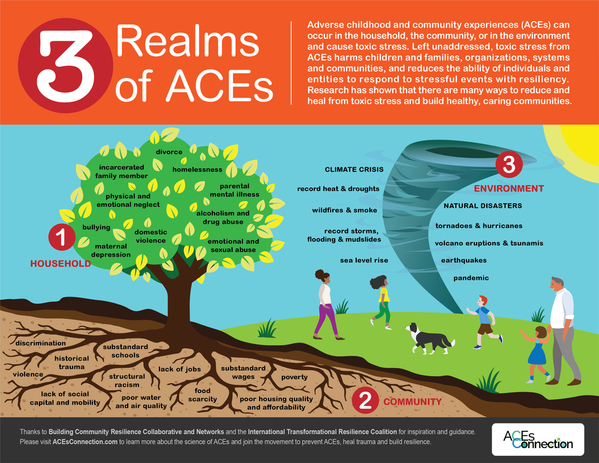

When we look at what gets in the way of well-being for clients, when we think about things like Adverse Childhood Experiences and their consequences, we often focus on the individual. Looking at this diagram, it’s evident that there are many factors that are systemic and structural that work their way into the mix of what is going on for our clients and ourselves.

It is possible to see that the barriers clients face are built into the systems that we work within and that we work to change. In other words, the barrier is not the client’s; rather, the system and structures generate the barriers. “Helping” the clients invites us to be advocates, challenging those very systems that impact our clients.

Power and agency in the career development process

Being in the helping profession puts us in an automatic position of power over: we are providing something to someone who does not have it. Just by doing this work we are in roles that put our agency, our actions, in the foreground.

The power structure is set up: clients come to us, in our offices or online spaces, where we have jobs, funding and programming. The power dynamic is real – and with it comes privilege.

Dr. Catherine Hajnal and Seanna Quressette will be co-presenting a session on “Trauma-informed Referrals: Being an Advocate in Your Community” at CERIC’s Cannexus24 conference, taking place virtually and in-person in Ottawa from Jan. 29-31, 2024. Learn more and register at cannexus.ceric.ca.

Power is positional. We may not feel like we have power, but the clients’ perspective of our role is that we do have power. When we offer “help” from this position, we are centring our own perspective. Decentring oneself invites us to consider other worldviews and experiences. This is in service of a shift from a power over to a power with dynamic.

One way to begin to address the power dynamic is to recognize that the client’s circumstance is not all on the individual. There are social determinants that are at play. There are very real systemic and structural barriers that clients face.

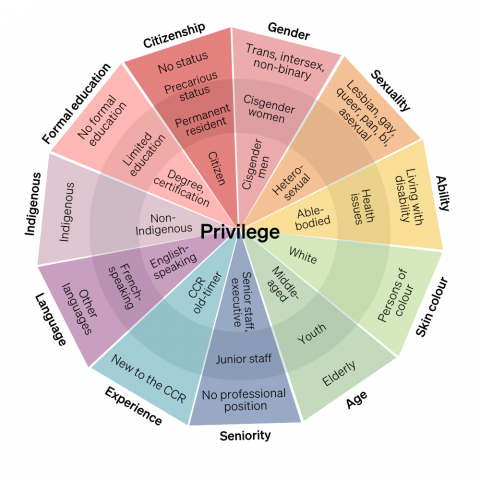

In the example Wheel of Power below we see various ways systems can affect an individual’s power/agency. Note that the closer you are to the centre, the more privilege you have in a white-centred, colonial context.

What we do with that power determines whether or not we are advocates for change. When we invite the individuals seeking our help into the role of doer rather than observer, when we engage with different perspectives and ways of knowing, we begin a power with conversation.

What does it mean to be an advocate for change?

The verb and noun “advocate” come from the notion to witness and to call. To advocate from a position of balance is to speak with. That requires the ability to stand outside our personal framework to see from another’s point of view.

The dance of power can be subtle. We want to shift away from the one-up power over dynamic, shifting from “advocate for” to “advocate with.” When we advocate for someone, this suggests we have more power than they do; if we are advocating with someone, then we are centring their voice as louder.

Working from a trauma-informed perspective is centred in the individual’s agency: “What do you need? What are three things that might help you right now? Which would be most useful?”

It is key to understand that when an individual can’t speak for themselves, very often the choice is made for them. Hopefully we know enough about the person’s circumstance to know what they may need. That said, it is empowering to ask what someone needs before presuming what they need.

“We want to shift away from the one-up power over dynamic, shifting from ‘advocate for’ to ‘advocate with.’”

One of our guiding principles is that we always assume trauma is in the room. Consider, for example, the context of moving from one country to another, which can be a traumatic experience. In Canada, newcomers often experience bias.

They are bombarded with questions about the validity of their education and language capabilities, which they may not know how to respond to. When their qualifications are repeatedly questioned in a power-over dynamic, it is easy for the client to dip toward self-doubt and depleted self-agency.

As career practitioners, we can start by acknowledging the bias present in our systems and structures. We can lay out choices and engage with the client to define those choices together. We must ensure choices are the newcomer client’s, not ours. This method of working allows us to advocate on behalf of our clients while still leaving the agency with them.

Humility

As we talk about the role of advocacy, we circle around to the notion of humility. Another guiding principle we use is to hold the questions: What is it I believe today that is equivalent to the notion that the world is flat? Where is my history biased? How am I biased?

Part of our obligation when working with clients is to continually make our unconscious biases conscious. This requires reading historical accounts in the voices of those whom we want to advocate with. We must also examine how we are interacting with others: Do you follow only like-minded voices online? Do you engage in uncomfortable conversations with people whose identity feels uncomfortable for you?

We have to be aware that we all have frames through which we see the world. If we want to advocate for systemic change, we must be aware of those frames; otherwise, we risk perpetuating the oppression inherent in our systems. We recognize that the models we use were created with a particular lens that is both time and power sensitive; as times change, how we position ourselves to those models needs to change. (For example, Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs – a model widely referenced in career conversations – has faced criticism from various cultural perspectives.)

We need also to look at ourselves through an evolving lens: What are the uncomfortable conversations you shy away from? If you don’t want to talk about suicide, mental health, emotions, there’s something underneath that – coming from our families, how we learn, where we’re from. We need to examine these frames to understand and illuminate our biases so that we can advocate for systemic change.

Ultimately, the role of the advocate is to be informed, humble and engaged in the world.

Douglas College is the Mobile App Partner for CERIC’s Cannexus24 conference.

Great article! Thanks