Canada is performing well relative to other OECD countries with respect to the quality of career guidance, but there is room to make the provision of services more inclusive and consistent. In a context of considerable labour market change, particularly for low-skilled adults, effective career guidance for adults can facilitate their employment transitions by enabling them to make informed choices about upskilling, retraining and professional reorientation. The new OECD study, Career Guidance for Adults in Canada, assesses the existing system of career guidance policy and provision, and puts it into an international perspective.

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to an unprecedented labour market shock in Canada and around the world, deepening existing divides and accelerating the change in skills demand. Two years after the onset of the crisis, the Canadian employment rate is back to its pre-pandemic level. However, long-term unemployment continues to be high even as skills shortages are reappearing in many sectors.

The pandemic has added to existing structural trends affecting skill demands, such as digitalization, population aging, globalization and decarbonization. The skills needs for jobs in growing sectors and occupations are not the same as those required for jobs in declining ones. The risk of job loss and lower incomes in new jobs increasingly falls on vulnerable adults such as those with low skills and qualifications. Against this background, career guidance has the potential to support an inclusive employment recovery by facilitating career transitions and bolstering labour market opportunities for vulnerable groups.

New OECD survey data shows that the use of career guidance services by adults in Canada is lower than in other countries where survey data is available. The reasons adults seek career guidance are different in Canada than elsewhere: more adults in Canada seek career guidance because they are looking for a new job (64% vs. 43% on average across countries in the survey), either because they are unemployed or because they are looking to change jobs.

In turn, Canadians are less likely than their international counterparts to seek career guidance when they are choosing a study or training program (19% vs. 31%), or when they want to progress in their current job (27% vs. 40%). About half of Canadians who do not access career guidance report that they do not need it, one in five say they are not aware of career guidance services and another 16% state that they do not have enough time due to work or family responsibilities.

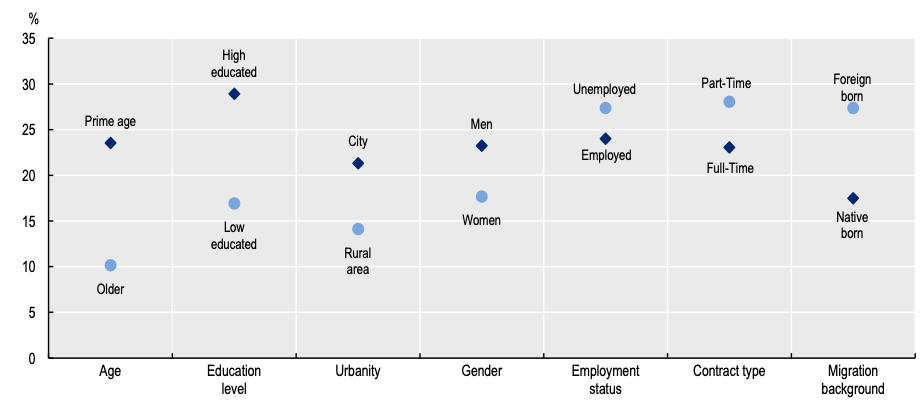

The use of career guidance is unequal

Figure 1. Share of adults in Canada who have used career services over the past five years, by socio-economic, demographic and labour market characteristics

The most crucial challenge for career guidance in Canada is making services more inclusive and targeted to vulnerable groups. Older and lower-educated adults, for instance, are much less likely to use career services compared with their younger and higher-educated peers (see the figure above).

As in other OECD countries, additional efforts are required to increase the take-up of services by adults who experience more complex and intersecting barriers to employment. In Canada, making service provision more inclusive is a particularly pressing issue: Canadian adults who feel negatively about their future labour market prospects are less likely to seek career guidance.

The type of provider chosen relates very closely to the employment status of adults. Unemployed adults are more likely to use government-run employment services that are provided by the provinces and have a job-matching focus. Employed adults are more likely to consult career services offered by private career guidance providers, although these come at a cost. Adults who are currently working in jobs with a high risk of automation tend to be lower-skilled and may not be able to afford or access these private services. Given the increasing pace of change in the demand for skills, reaching out to workers ahead of job loss is crucial.

The quality of existing career guidance services in Canada is relatively high. Adult users of career guidance services in Canada are generally satisfied with the guidance they receive and the training and employment opportunities it provided. Ongoing efforts to professionalize the field of career guidance should help to maintain this strong performance in the future.

At the same time, services could be more consistent, both across and within provinces and territories. Well-designed systems of service management and outcome monitoring can support quality in career guidance provision, including through public procurement and outcome-based funding.

Drawing from this analysis and international best practice, a number of key policy directions are put forward to improve career guidance for adults in Canada:

- Experiences from different OECD countries have shown that engaging vulnerable adults requires active outreach in their communities and workplaces, as well as better targeting of career guidance services to address their needs. While such services may be costly, this investment contributes to lower and shorter unemployment and a better-skilled workforce. A more proactive approach entails building the capacity of government-funded career guidance providers to provide guidance not only to unemployed workers, but also to employed workers who are at risk of losing their jobs due to automation or the green transition.

- Stronger co-ordination across and within provinces and territories on career guidance policy could help formulate better policy strategies and make service provision more consistent. Improving co-operation between training providers, government-run employment services and employers would promote the provision of career guidance that is tailored to labour market needs.

- Supporting the professional community of career guidance practitioners in Canada is key to maintain the effectiveness of services. Continuing professional training for career guidance practitioners, particularly related to the use and interpretation of labour market information, is important. The current initiative of a federal-level competence profile and certification of career guidance advisors is a promising step to further professionalize the field.

To read the report, visit Career Guidance for Adults in Canada. Register for the report launch webinar, hosted by CERIC, to watch live on Feb. 28 or to receive a recording.