I was keen for the release of the results of CERIC’s 2019 Survey of Career Service Professionals practitioner survey last January for two reasons. One, I was looking for a refresh on the Canadian Career Practitioner big picture – an updated snapshot of our field. Two, I wanted to see how the results compared to my regional professional context in Atlantic Canada. The survey provided an opportunity for me to check my assumptions with up-to-date data and validate what I know to be true of career development practice. It is interesting to reflect on the results now, under the weight of a global pandemic, where Canadians have gone from being stressed about finding decent work and making the right decisions along the way, to collective social and economic fears about the future.

National picture

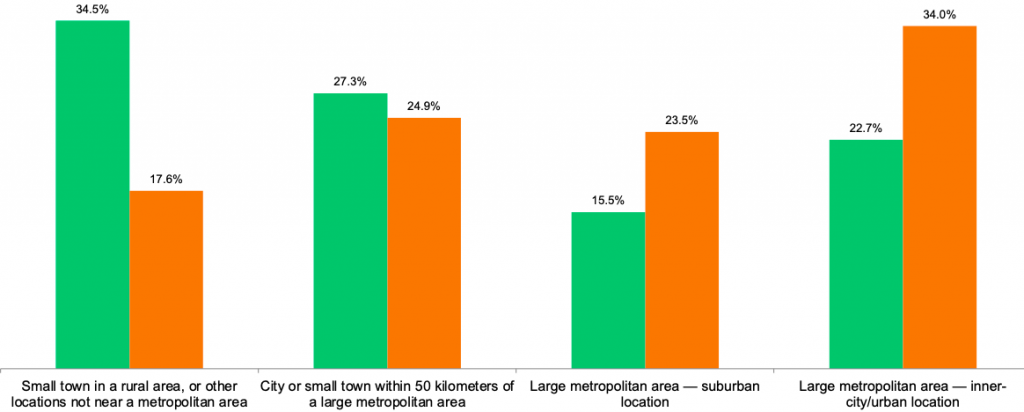

The career development field is predominantly women (82.6% nationally); a group of largely university-educated professionals who have studied in the areas of career development, education, counselling and/or psychology fields. Geographically, we are working in metro areas or small cities or towns within proximity to larger cities. We work in post-secondary, private sector or non-profit roles with annual salaries between $40,000-$85,000 per year. Only a quarter have less than five years of experience. Career development practitioners (CDPs) are experienced. Many have been working in the field for decades and see themselves as continuing to do the work; they are in it for the long haul, which I know deeply will be key to social and economic recovery in the next year or more.

This article is part of a series exploring the regional results of CERIC’s 2019 Survey of Career Service Professionals amid our new reality. Read more:

Regional view

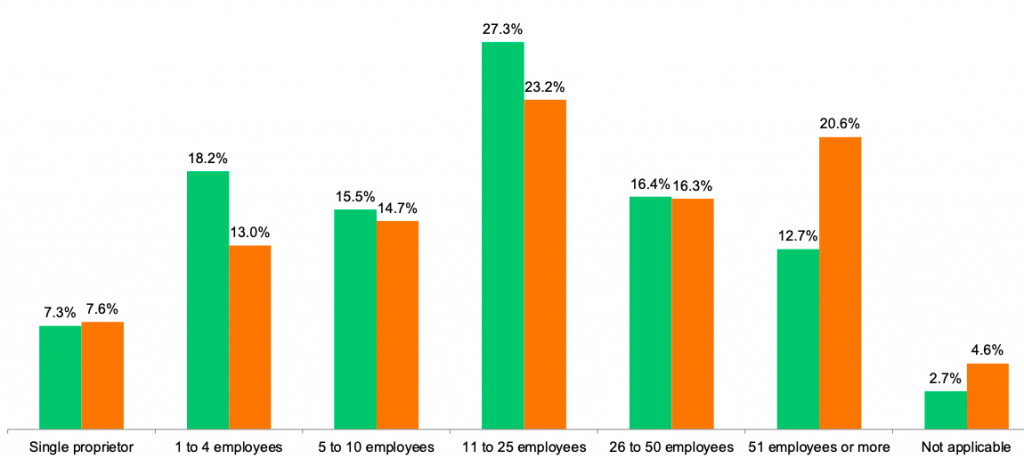

Data for the Atlantic region differs somewhat and sounds a lot like a story that I hear from CDPs practising in small settings. It goes something like this: “Where I work and how I do my job is different than everyone else.” More CDPs in the Atlantic provinces work in the non-profit sector (61.8%), in small departments or organizations, with the vast majority of those workplaces having fewer than 26 employees (68%). Most work in towns or rural areas (approximately 62% Atlantic vs 43% nationally) that are spread out. This made me think of two CDP colleagues who work over 1,000 kilometres away from each other in Stephenville and Goose Bay, NL.

How would you describe the area where you are located?

Size of careers services organization (including departments and satellites)

This also reflects what I saw in my CDP consultations in St. John’s, Grand-Falls-Windsor and Corner Brook, NL, this past fall. The visits were intended to gather input to shape a renewed Competency Framework, updating the Standards and Guidelines for Career Development Practitioners. Practitioners were working in small teams of fewer than five staff with their work attached to community development or government services. They were energized to be in a room together discussing their profession, hearing updates from the Canadian field and sharing how they were practising career development. They shared often feeling professionally isolated, a deep responsibility to their work and reported that their work was equally challenging as rewarding. What is more often required in these professional contexts is the role of the expert generalist rather than a specialized practitioner or niche services provider. This is reflected in the data in higher offering of one-on-one supports being offered in Atlantic Canada in contrast to group sessions. Let me pause here to offer an enthusiastic fist bump to youth employment facilitators who so frequently are tasked with wrangling group intake on impossible timelines. This requires mobilizing great professional networks across multiple service sectors.

Curiouser and curiouser

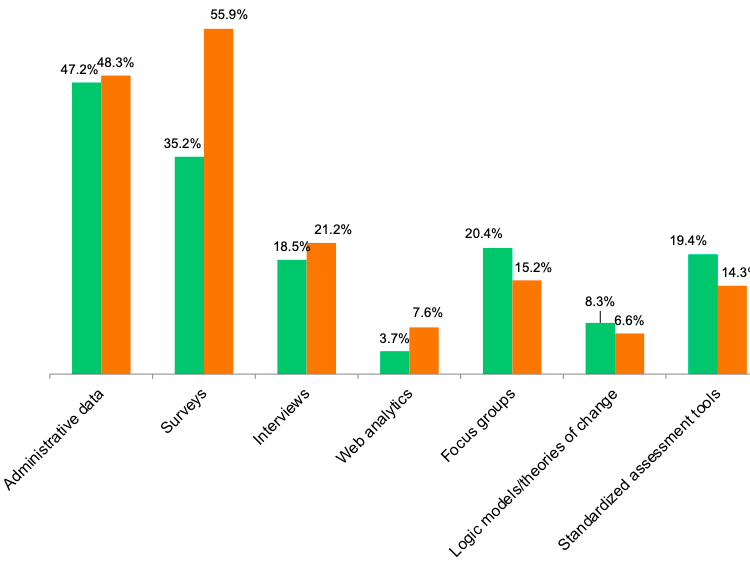

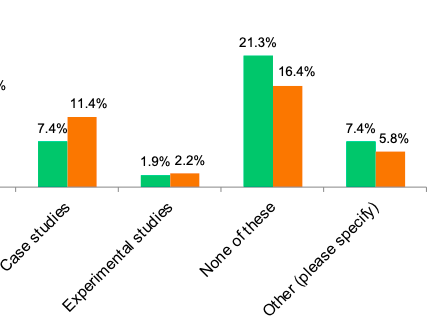

The findings on evaluation and research caught my attention. Atlantic practitioners are generally lower than the national average for most evaluation activities, with the exception of focus groups and standardized assessment tools. At the same time, they are engaged in more types of research activities compared with the national results. This makes complete sense to me. I see research and evaluation as part of the same continuum that is seeking proof of the impact of career services. How a team decides to find answers to research questions is best achieved within the specific practice context. For example, you would never use an online survey unless you had huge numbers of individuals to draw from. I learned from a Canadian Evaluation Society survey design course to expect an estimated at 15% return rate on surveys. CDPs in smaller settings dig into administrative data and use focus groups and informant interviews. The difference in these approaches I believe is a result of CDPs knowing how their communities work.

What methods do you currently use to evaluate the impact of your career counselling/career development programs or services? (Check all that apply)

My role is supporting practitioners and collaboration. What I have been hearing more often is a desire to move away from working harder and being busier as the metric for a good work day. My thought is that in 2020, the mounting regional, national and international considerations are taking up all of our mental space. Practitioners want to use their time wisely and not waste time defending their field or arguing about the impact of their services – they have better things to do. In Newfoundland and Labrador we have a handful of community-based research projects currently under way that are providing new insights and proof of promising practices that are regionally contextualized.

Shifting realities of 2020

Canadians are stressed about finding decent work and making the right decisions along the way. Since the onslaught of COVID, these fears have become our collective reality. The field of career and employment services are bracing themselves for heavier caseloads and more challenging career conversations, all the while desperately trying to keep up to date on platforms to support virtual delivery, available social support, and information about the opportunities for learning and work.

The big picture is a field of educated and experienced professionals who have seen plenty of shifts in society and economy. They are committed to what they describe as challenging and rewarding work. Our regional snapshot confirms what we believed all along; practitioners have decades of experience to lean on and are confident about how to adapt to their regional context while balancing on a constantly shifting social and economic realities in 2020.