|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

As a neurodivergent, racialized first-generation student and immigrant, I had to overcome many intersecting barriers to education and career. Due to these experiences, I have an intersectional perspective on workplace accessibility and inclusion. I believe this awareness of multiply marginalized people’s experiences is key to creating high-impact accessibility.

My mind has always been more visual, so I’ve included the following images to help tell my story in a way that feels more natural to me.

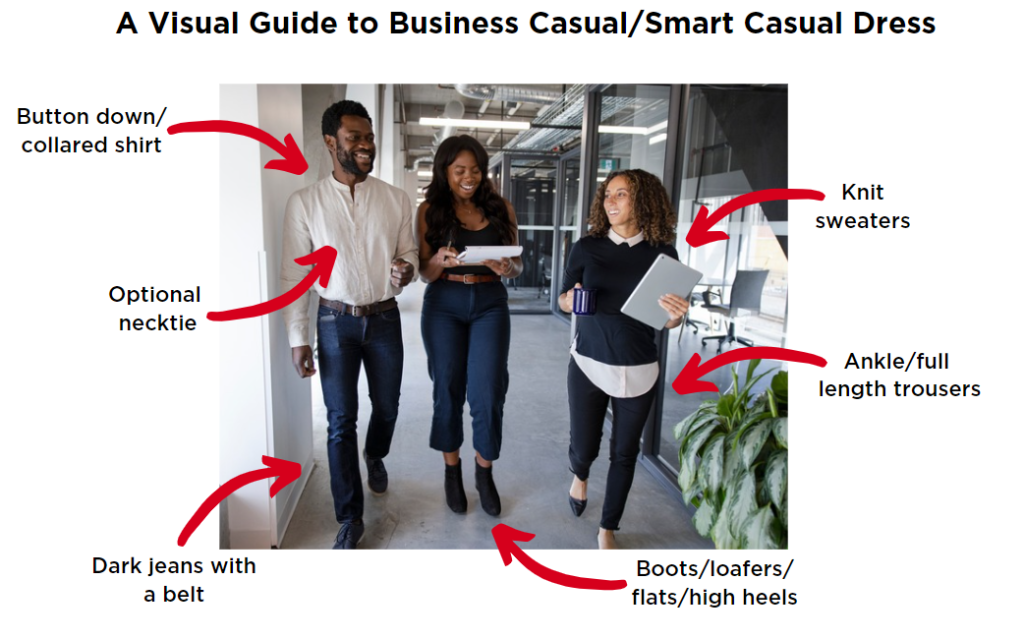

As a first-generation immigrant, I didn’t have parents with lived experiences of work and school in Canada. This meant that they weren’t able to guide me on what to expect in post-secondary education or in the workplaces that followed. Looking back, early educators didn’t think to provide me with resources to bridge this gap because of their low expectations of me. I had a harder time reading the cultural cues that others seemed to pick up more intuitively because I am neurodivergent. As a result, I learned to navigate implicit expectations like project prioritization, writing tone for school versus work and workplace attire with less support.

Experiencing multiple barriers led to imposter syndrome, which made me question whether I deserved all the sacrifices my parents made for me to grow up in Canada. When I would join a workplace with no understanding of what to do and how to act, I was often made to feel like I didn’t belong there. But working with the University of Calgary’s Work-Integrated Learning for Neurodivergent Students Initiative showed me that it doesn’t have to be this way.

Interventions that align with universal design principles help create environments that are inclusive without individuals needing to disclose personal experiences to access accommodations. For example, providing charts or examples of appropriate workplace attire, like the one below, can help many different people. Resources like these can help neurodivergent people who might need information communicated visually, as well as first-generation students and immigrants who may not have members in their community who are knowledgeable about specific workplace cultures.

Being thoughtful about the implied culture in a workplace by offering clear guidance can help to bridge support gaps that marginalized people experience. Consider how you might demonstrate the writing tone expected for a workplace newsletter versus a report to the organization’s leadership team. Consider providing samples of past work, or a glossary of common acronyms and jargon.

“Let yourself be curious and view people from a strengths-based perspective.”

Also, think about how you might provide this information in multiple ways and feel free to ask people how they want to receive this information (e.g. verbally during meetings or written down in an email). This is both neuro-inclusive and helpful for those whose primary language is not English. To that point, consider how you might work with the unique strengths and passions of each individual. Let yourself be curious and view people from a strengths-based perspective.

Most importantly, brainstorm ways you can facilitate conversations about accessibility and model an openness to having those discussions. Starting the conversation around support and workplace accommodations can make having that conversation less intimidating. One of the most impactful supports I have received was the openness of my workplace mentors in discussing the barriers they have experienced, which normalized my experiences. This vulnerability and awareness of inequities also challenges imposter syndrome by normalizing the learning curve anyone can expect in a new workplace.

Creating a culture where other people with similar experiences can openly share and support each other can also create accessibility for the multiply marginalized. Offering a workplace touchpoint/mentor with shared experiences, using clear language without slang or unexplained jargon, and inviting questions without judgment is an important part of creating such a culture.

Using the tips above might only require a small pivot from you but can have a big impact on a lot of different people. Remember, you don’t have to be an expert on everyone; that’s impossible. What matters most is being flexible and open to change.